The Coastline Paradox: Why AI Won’t Kill Software Engineering

View PDF- Stefano

- AI , Software Engineering , Economics

- 01 Jan, 2026

In 1951, Lewis Fry Richardson was trying to measure borders.1 Not for political reasons---Richardson was a pacifist mathematician interested in predicting wars, and he suspected that the length of a shared border might correlate with conflict probability. Simple enough: look up the lengths of various national boundaries and run the statistics.

Except the numbers didn’t agree. Spain and Portugal, sharing the same border, reported different lengths. Not by a little—by 20%. How could two countries measure the same line and get different answers?

Richardson discovered something unsettling: they were both right. The border between Spain and Portugal isn’t a fixed length. It depends on how you measure it. Use a coarse ruler, and you get a short border. Use a finer ruler, and the border grows.

Today, software developers face a similar puzzle. AI appears to be a “perfect ruler” that will finish measuring the coastline of code, rendering human programmers obsolete. But this fear rests on a false assumption: that the demand for software is a fixed quantity, fully visible at today’s prices. What if, instead, AI is simply a finer ruler—one that will not complete the job, but reveal latent demand we couldn’t see before?

The Fear

If you’re a software developer in 2025, you’ve heard the predictions. AI will write code. AI will debug code. AI will architect systems, design databases, optimize algorithms. The logical conclusion seems obvious: fewer programmers needed. Perhaps eventually none at all.

The argument has a seductive clarity. If an AI can do in seconds what takes me hours, and if AI keeps improving, then at some point I become redundant. The world needs a fixed amount of software—call it 100 units. Once AI can produce those units instantly, the human role vanishes. I become surplus.

This logic is intuitive, which is why it’s dangerous. It treats software like a gold mine: a bounded resource that can be fully depleted. Measure the coastline once, and you’re done.

But what if the demand for software isn’t a mine? What if it’s a coastline?

The Paradox

Picture the coastline of Britain. Measure it with a 100-kilometer ruler—skip from headland to headland, ignoring the bays—and you get roughly 2,800 kilometers. Now use a 50-kilometer ruler. The shorter ruler can trace into the bays, around the peninsulas. The coastline grows to 3,400 kilometers. Use a 10-kilometer ruler and it grows again. A 1-kilometer ruler captures the inlets, the harbors, the tidal pools. A 1-meter ruler picks up the rocks.

There is no convergence. As your ruler shrinks, the coastline lengthens—without bound. The “true” length of Britain’s coast is, in a meaningful mathematical sense, infinite.

This is Richardson’s coastline paradox, later formalized by Benoit Mandelbrot as a property of fractals.2 Fractal curves have detail at every scale. Zoom in, and you find more structure to measure. The act of increasing resolution doesn’t finish the job; it reveals more job to do.

Mandelbrot didn’t just say the coast was infinite; he assigned it a number called a fractal dimension. A straight line is 1-dimensional. A smooth plane is 2-dimensional. But the coast of Britain behaves like it is 1.25-dimensional3—so irregular, so self-similar at every scale, that it occupies more space than a line but less than a plane. The dimension quantifies the “wiggliness,” the rate at which measured length increases as the ruler shrinks.

The Historical Pattern

If the coastline theory is correct, we should see it in history. We do.

In 1865, the economist William Stanley Jevons observed something counterintuitive about coal consumption in England. James Watt’s steam engine had made coal use dramatically more efficient—you could extract more work from each ton. Classical reasoning suggested that England would therefore need less coal overall. The opposite happened. Because coal-powered work became cheaper per unit, people found more uses for it. Factories multiplied. Railways expanded. Ships converted from sail. The more efficiently coal could be burned, the more coal England burned.4

A century later, the same pattern appeared in software. In 1957, FORTRAN arrived.5 For the first time, programmers could write in something resembling human language and have the machine translate it to opcodes. The old guard was alarmed. Hand-coded assembly would always be more efficient, they argued. But more importantly: if machines could write machine code, what would happen to the people who wrote machine code?

What happened was this: the cost of producing a unit of functionality dropped. Dramatically. A program that took weeks in assembly could be written in days in FORTRAN. The price of software fell. And demand exploded.

At the “assembly language price point,” only governments, banks, and large corporations could afford software. Entire categories of potential users couldn’t reach the threshold. When FORTRAN lowered that threshold, those latent users materialized. Industries that had never computerized began to computerize. Problems that had never seemed like software problems revealed themselves as software problems. The number of programmers didn’t shrink. It grew by orders of magnitude.

The same pattern repeated with each productivity leap. Structured programming. Object-oriented languages. Garbage collection. Frameworks. Open source. Stack Overflow. Cloud infrastructure. Each time, veterans worried that the profession was eroding beneath them. Each time, the profession grew.

Economists call this induced demand, or the Jevons paradox. Efficiency gains don’t always reduce consumption. When demand is elastic—when there are latent uses waiting for the price to drop—efficiency gains increase total consumption.

The Assumption We Are Making

Before we apply this pattern to AI, we must be explicit about our central assumption: the Jevons paradox only holds when demand is elastic.

Elastic demand means that when the price drops, people consume substantially more. Not everything works this way. Consider salt: if the price of salt fell by 90%, you would not buy 90% more salt. You need a pinch for your soup, and that’s that. Efficiency in salt production destroys salt-production jobs—the demand is inelastic, effectively capped by need.

Light, by contrast, was elastic. In the 1800s, illumination was expensive: candles, oil, labor. People went to bed early. Cities were dark. As lighting technology improved—gas lamps, then incandescent bulbs, then LEDs—consumption didn’t plateau; it exploded. We didn’t just light the one room we had always lit. We lit streets, stadiums, billboards, screens. The demand was never “one candle per room.” The demand was “as much light as we can afford.”

Our argument rests on the claim that software is like light, not salt. There is no fixed quantity of automation, analysis, or digital capability that humanity “needs.” There is only a frontier of what is economically viable at current prices. Drop the price, and the frontier expands. Drop it again, and it expands further. The latent demand for software—for custom tools, for automation of tedious workflows, for solutions to problems too niche to justify today’s costs—is, we argue, practically unbounded.

But there is a second objection, more subtle and more dangerous.

Coal Is Not Miners

Jevons showed that England burned more coal as efficiency rose. He did not prove that England employed more miners. This distinction matters.

If demand for coal increases 10-fold, but mining technology makes each miner 100 times more productive, you still lay off 90% of your miners. The resource is consumed in greater quantities; the workers are not. Increased consumption and increased employment are not the same thing.

Does this break our argument? If AI makes each programmer 100 times more productive, and demand only grows 10-fold, we should expect mass displacement regardless of how elastic the demand is.

The answer requires us to examine what, exactly, AI makes more efficient—and what it leaves untouched.

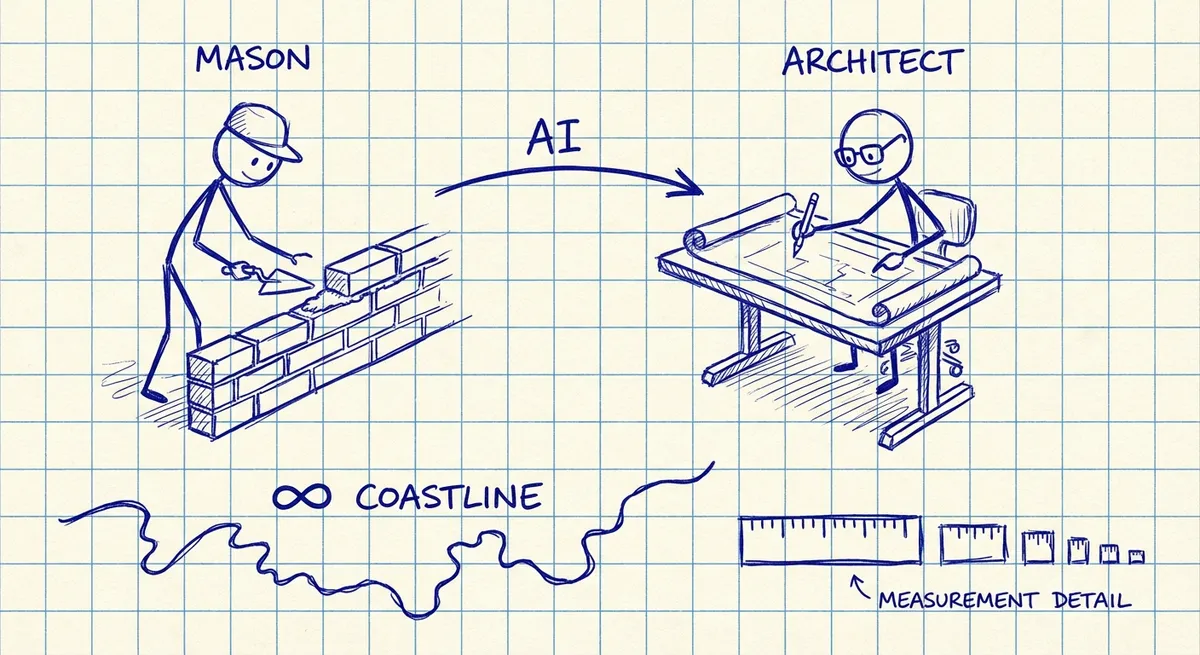

From Mason to Architect

AI is not a uniform productivity multiplier across all programming tasks. It is spectacularly effective at one thing and relatively weak at another. Understanding this asymmetry is essential.

Consider the distinction between two claims:

Claim A: AI can produce working code from natural language descriptions.

Claim B: AI can produce production-quality systems from natural language descriptions, without skilled human oversight.

Claim A is already true and will become more true. Claim B is much harder.

The gap between “code that runs” and “code that should run in production” is vast. It includes: security considerations that don’t appear in the requirements, edge cases that no one mentioned, performance characteristics that matter under load, maintainability for the next developer, compliance with regulations the user doesn’t know about, integration with systems the user can’t fully describe, and graceful degradation when dependencies fail.

A non-programmer can prompt an AI to build an expense tracker. They cannot prompt an AI to build a multi-tenant SaaS with proper data isolation, audit logging, GDPR compliance, and circuit breakers—because they don’t know those concepts exist. They don’t know what questions to ask.

Here is the crux: AI has inverted the economics of software production. Generating code is now cheap. Verifying code remains expensive. The marketing manager can get a working prototype in an hour. But is it secure? Does it handle edge cases? Will it scale? Does it leak memory under load? Answering these questions requires understanding that the AI doesn’t have and the marketing manager doesn’t have either.

This is why the coal-versus-miners objection does not sink our argument. If the steam engine had made extracting coal cheap but left finding, planning, and managing mines just as labor-intensive, the mining industry would not have shed workers despite the productivity gains. The bottleneck would have shifted, but the work would remain.

This is precisely what is happening in software. AI is the steam engine for code generation—it makes the extraction cheap. But the upstream and downstream tasks—understanding what to build, verifying that it works correctly, integrating it into existing systems, maintaining it over time, reasoning about security and performance—remain expensive and human-intensive. These are not “syntax typing” tasks. They are judgment tasks, context tasks, responsibility tasks.

In the past, a developer was paid to lay bricks—to write syntax. In an AI world, the bricks are free. The value shifts to the design of the cathedral: to architecture, integration, verification, and the translation of ambiguous human intent into precise technical requirements.

There is an economic principle that captures this shift: Baumol’s cost disease.6 When productivity rises dramatically in one sector (say, manufacturing), wages rise across the economy. But in sectors where productivity can’t rise as easily—live performance, complex judgment, bespoke design—the relative cost explodes. As the cost of generating code approaches zero, the value of the things AI cannot do will disproportionately increase.

The developer of 2030 probably writes less code directly. They spend more time specifying intent precisely, validating AI output, debugging subtle issues that AI introduces, and translating between business problems and technical solutions.

This is not unemployment. It is evolution from mason to architect.

The Infinite Coastline

Now we can see the full shape of what’s coming.

At the 1957 price point, only the headlands were visible: military systems, banking, airline reservations. At the 1980 price point, the bays emerged: accounting packages, inventory systems. At 2000, the inlets: e-commerce, social networks. At 2020, the tide pools: no-code apps, internal tools. Each drop in price revealed demand that had always existed but couldn’t be satisfied.

And now, at the AI price point, we are reaching for a finer ruler still. The bakery gets its demand-forecasting model. The nonprofit gets enterprise-grade automation. The researcher gets a bespoke pipeline. But each of these still requires someone to integrate, validate, and maintain—because AI has made extraction cheap while leaving judgment expensive.

Not every programmer will thrive. Those who define their value as “writing syntax” will struggle, just as assembly programmers struggled when they refused to learn FORTRAN. The masons who insist they are only masons will be displaced. But the masons who become architects will find more work than ever.7

We used to think the market for software was a fixed border we could fully map. Richardson taught us otherwise. The “true” length of a coastline depends on the resolution of your tool—and we have just been handed the finest ruler in history.

Footnotes

-

Richardson published his findings in “The Problem of Contiguity: An Appendix to Statistics of Deadly Quarrels” (1961). His work on border lengths was posthumous—he died in 1953, and his papers were edited and published by Quincy Wright and C.C. Lienau. ↩

-

Benoit Mandelbrot’s The Fractal Geometry of Nature (1982) remains the canonical text on fractal mathematics. Mandelbrot explicitly credited Richardson as the discoverer of the coastline effect and developed the mathematical framework to explain it. ↩

-

The exact value depends on measurement methodology. Mandelbrot calculated Britain’s west coast at approximately 1.25; other estimates range from 1.21 to 1.30. The key insight isn’t the precise number but the fact that it exceeds 1—the coastline is “more than a line.” ↩

-

Jevons elaborated this in The Coal Question (1865). For a rigorous modern treatment, see Blake Alcott’s “Jevons’ paradox” in Ecological Economics (2005), which examines the conditions under which efficiency gains lead to increased rather than decreased resource consumption. ↩

-

The Computer History Museum has an excellent oral history of FORTRAN’s development and reception. John Backus, FORTRAN’s lead designer, later recalled the skepticism: many programmers believed that machine-generated code could never match hand-tuned assembly. They were right about efficiency; they were wrong about what would matter. ↩

-

William Baumol and William Bowen introduced this concept in Performing Arts: The Economic Dilemma (1966), originally to explain why symphony orchestras faced perpetual financial pressure. The core insight—that productivity gains in one sector raise costs in sectors where productivity can’t improve—has proven remarkably durable. ↩

-

David Autor’s work on task-based labor economics, particularly “Why Are There Still So Many Jobs?” (Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2015), provides the most rigorous modern framework for understanding automation’s effects on employment. His central observation: automation tends to create more tasks than it destroys, though the new tasks often require different skills than the old ones. ↩